COVID-19: The Case of Coastal Ecuador

By Maja Jeranko

Maja Jeranko is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

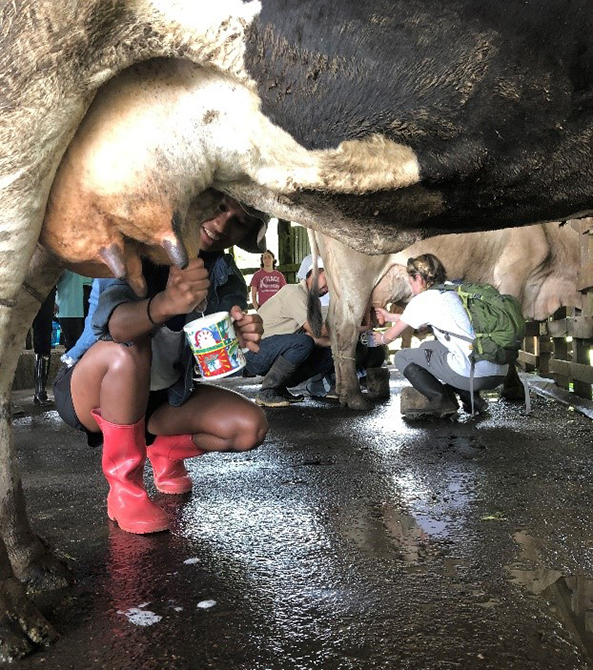

Ecuador Image – Taken by Maja Jeranko in Don Juan, Ecuador.

Don Juan is a small fishing village on the Pacific coast of Ecuador in the Manabí region. This place of about 300 families with an average of three children appears idyllic at first: small fishing boats sit on the sandy beach, waiting to take men fishing at 3 am; a children’s library made of bamboo offers an incredible selection of books and activities to all community members; a wooden house known as “Casa Comunal” comes to life three times a week when local women get together to dance to the rhythms of reggaeton and salsa. In the heart of the village, a settlement of 60 identical houses that were built after the 2016 earthquake destroyed 98% of existing infrastructure, offers a reminder that a traumatic event forever changed the lives of people in this quiet rural village.

I have been conducting research in Ecuador every summer since 2016, mostly on topics related to gender-based violence. On January 19, 2020, I went to Don Juan to conduct anthropological dissertation research and focus on how post-earthquake initiatives continue to impact gender relations and the daily lives of women. I felt confident about the year-long plan we made with my local collaborators about what my role as a researcher and a volunteer at A Mano Manaba Foundation would be. However, just as I began to ease into the slow-paced life, the threat of COVID-19 began to lurk.

Like most things in the news, many believed that Don Juan was immune to what was happening in the world. That was the beauty of living in a small isolated area. There were barely any cases of COVID-19 in Ecuador, so there seemed to be few reasons to worry. People were more concerned about the torrential rain that has been unusually strong during this rainy season, flooding people’s precarious built homes and causing roads to collapse. People were evacuated due to increased river tides and most ended up temporarily living in the elementary school or the “Casa Comunal”. The local mayor informed people that there are no funds to build safer homes, which meant that many would build another unauthorized wooden or bamboo structure near the river that would eventually get flooded. And so the cycle repeats.

Ecuador Image – Taken by Maja Jeranko in Don Juan, Ecuador.

At the very beginning of March, one of my friends in Don Juan returned from his trip to Quito and joked about people wearing masks on the bus and buying into the panic. He joked that he coughed on purpose just to freak out his fellow passenger. He was far from worried: “This virus has nothing on me! We grew up in mud and dirt … This is something that you, white people, should be worried about!” This lead to a light conversation about the origins of the virus but most of the volunteers were unbothered by the global pandemic in the making, even though some of us had close family in places around the U.S. and Europe that were becoming the global epicenters.

That same week, I began to receive unsettling messages from my loved ones in Slovenia, where they just entered the national lockdown in hopes of avoiding the disaster that was unfolding in neighboring Italy. As there were still less than 50 confirmed cases in the entire country, I concluded that things weren’t that bad. Shortly after, I decided to take some time off my research and spend a week in Quito. I packed a scarf and white vinegar (I could not find any masks or disinfectant in the village), only to arrive in the national capital where I received a sharp reality check on the state of the pandemic. COVID-19 was definitely no laughing matter in Quito. The friend I was staying with asked me to change from my outside clothes the minute I came into the house—to prevent any possibility of a lingering virus—and asked me to wash my hands profusely lest I touch any food at all with hands that may have touched surfaces where viruses are known to linger. Though people were worried, we were reassuring each other that there are practically no confirmed cases and the state is already taking precautions.

I had to go for a routine doctor’s checkup to obtain a health certificate for my Ecuadorian visa. My friend found a pack of masks in her house from the time volcanic eruptions were a public health concern and I put one on, just in case. I went to a small clinic where a male doctor mocked my use of a mask: “Niña, in our culture people, will be freaking out by seeing a white woman using a mask. They will assume that you are sick. Don’t buy into the panic!” It was only a few days later that the country went into full lockdown. It was only a few weeks later that the national health and funeral services began to collapse.

During the week of March 6, I still felt like staying in Ecuador was the safest decision, so I decided to return to Don Juan as soon as possible. While the number of cases was rising, there were still none in Manabí province, and we were hoping it would stay that way. Many people from Quito had told me that “costeños” never respect the rules anyway, so they wouldn’t stay inside even if it came to that—a stereotype about the Ecuadorian coastal culture that would later prove to be false.

Regardless, I decided to return to Don Juan that week to wait until the crisis passes in my small bamboo house. As there were few cases, I assumed that we would not need a strict lockdown, thus I would still be able to conduct my research. On March 12th, the government announced a full lockdown within 24 hours. The panic was palpable and it became clear that it was going to be impossible to do fieldwork in these conditions. Research can seem invasive in and of itself but trying to approach people in times like these seemed particularly inappropriate. With no research to focus on, being isolated in a small village for an indefinite period, with the closest hospital located 2 hours away, my continuation of research no longer seemed like a viable practice. I consulted with my local collaborators and I decided to take the next flight home. The next morning, I packed some essentials and left the coast, assuming I’d be gone for a month or so.

My plan was to catch a flight from Quito to Fort Lauderdale on March 17. I decided to go to the U.S. where I have friends and family rather than attempt to fly across the Atlantic to Slovenia. This was the last day when intra-provincial transport was allowed and I was paralyzed from anxiety that international borders would close before I would reach my destination. My fears came true: about three hours into my bus ride, my flight was canceled, because of the closing of borders. I used my spotty internet to book another flight that was also canceled right after. I was finally able to secure a direct flight the next day. That same night, the country announced a suspension of all international flights starting at midnight the next day, March 17. My flight was at 2 a.m., so I missed my chance to get to the U.S. by two hours, with no available flight insight.

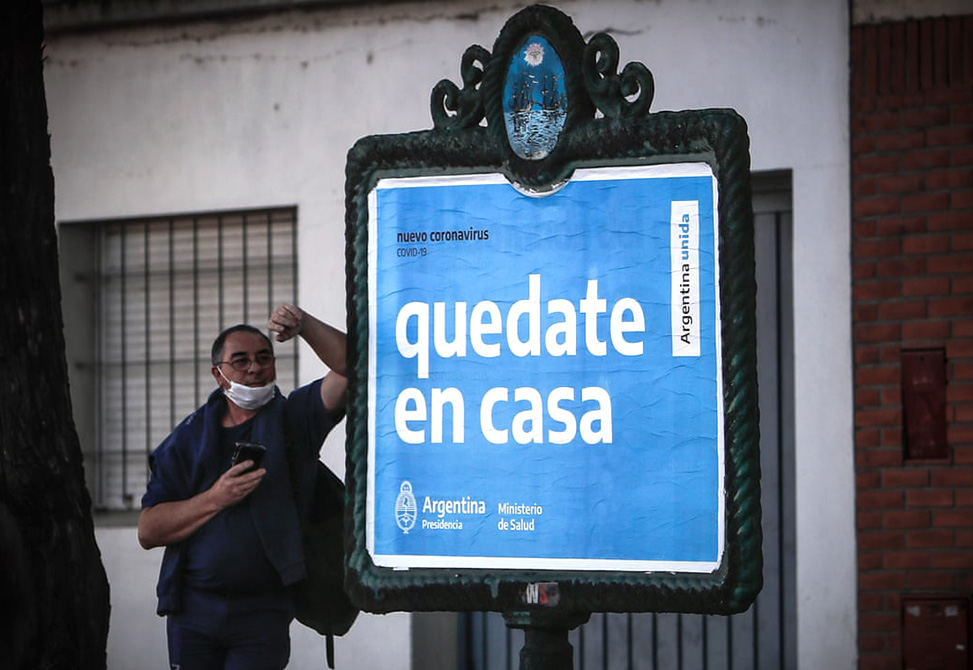

I embraced the fact that I was stuck in Ecuador indefinitely, and fortunately, my friend generously welcomed me into her house indefinitely, a privilege that not too many field researchers would have. Quito turned from a vibrant metropolis into a quiet, empty city surrounded by the beautiful Andean scenery, and only a few open food markets. Curfew rules were changing daily, and soon we were only allowed to leave the house for a limited amount of time on limited days. The curfew got stricter and ordered people to stay inside between 2 pm-5 am, with police and military guarding every corner to make sure rules were obeyed.

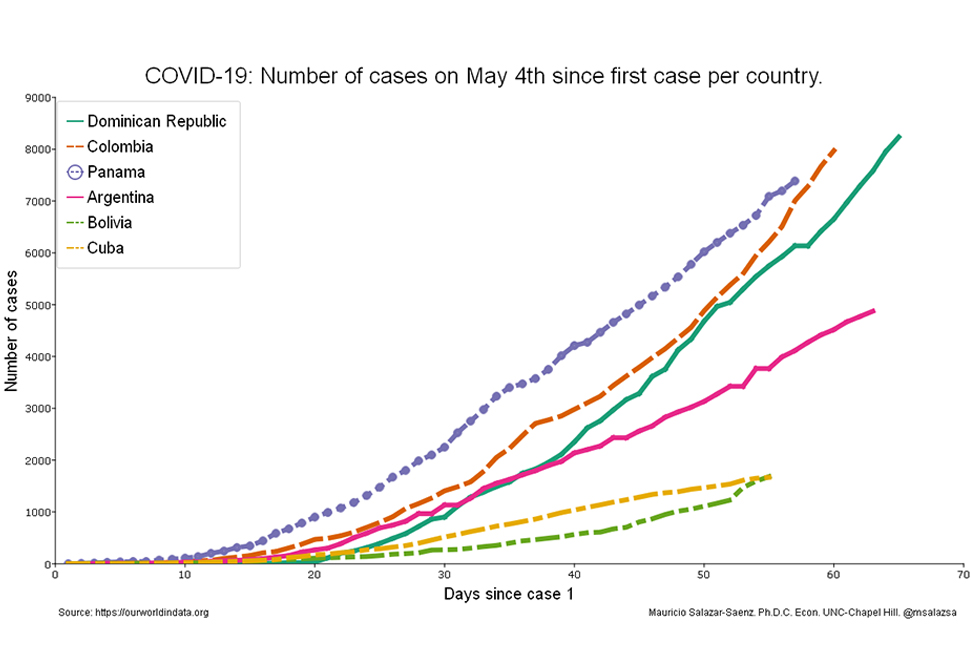

A few days later, I began to receive news about repatriation flights to Europe as Slovenian Embassies across Latin America began to reach out to me, advising me to get on one. At that time, Europe was still the epicenter of the pandemic and the idea of spending several days on international flights and European airports seemed unthinkable. They argued that Ecuador might collapse when the pandemic really hits: “You should consider that if Europe is struggling, imagine what will happen in Latin America.” Years of critical social education cautioned me not to give into potential Eurocentric beliefs, so I took those comments with a grain of salt and I asked myself what more could have happened in Ecuador after all to execute safety measures appropriate for their context. While I was still convinced that Ecuador did a good job of enforcing restrictions, I began to realize that the crisis wouldn’t end anytime soon, I decided to go be with my family in a place where I have secure health insurance.

On March 20, I boarded a repatriation flight back to Slovenia. Each step was a struggle: My friend was not sure whether she could take me to the airport, because we were receiving mixed information about whether or not she was allowed to travel for non-essential purposes. I decided to get a taxi, which is usually a painless task, as Quito is filled with them. However, due to mobility restrictions, it was impossible to find a one, but I was eventually lucky to get help from my colleague who works in the tourism industry who made sure I got there on time. The Slovenian Embassy in Brazil sent me a salvoconducto (safe-conduct) signed by the minister of external affairs that allowed me to move around the city. We had to show that along with my confirmed ticket to several police officers before we were allowed to get anywhere near the airport. The airport was very quiet, only people who were boarding the same flight as me were lined up at the entrance.

Our flight was packed with European citizens and I was surprised to notice that the atmosphere was eerily calm. In-flight instructions avoided pandemic-related discourse but warned us that flight attendants would operate with minimum contact. There were no specific instructions on sanitation. I did not find their service very different from “normal”, though the only served closed-bottles or cans to us. I noticed that more people than usual sanitized their trays and handles of the seat, but we were not encouraged to do so. An occasional cough made everyone nervously look at each other, but the majority of people fell asleep minding their own business. Once we got to Amsterdam, we passed through security rather quickly, without getting screened. Usually a vibrant international port, Amsterdam Airport was completely empty without a single open store, which was frustrating once I got hungry. I managed to take a brief nap on one of the comfortable chairs, feeling hopeful that I would soon be boarding a flight to Zagreb, Croatia, and get home.

A few hours later, as I turned on my phone, I learned that Zagreb was shaken by a 5.3 magnitude earthquake, with serious infrastructural damage. The feeling of being so close to the finish line only to be told that another thing went wrong was mind-boggling. It felt sobering and humbling to be reminded that no matter how much we try to defy the basic laws of nature and control the outcome, tomorrow is ever the same as today. Passengers at the gate were similarly confused and worried, calling their loved ones in Croatia to see what was going on. The flight was delayed first by 30 min, then by one hour, two hours, and finally by four hours.

Eventually, we were able to leave on a very packed flight. There was no service on the airplane, only instructions on the changes made about security. We had to undergo an extensive interview about where we were coming from and where we were going, and I was only allowed to pass calmly because I was going to Slovenia—otherwise, I would have to spend 2 weeks in Croatian quarantine at my own expense. I took a taxi to the Slovenian border where my family was waiting for me. The taxi driver was telling me about his experience with the earthquake earlier that morning while warning me that I am in for a long medical exam at the border. Luckily, there was no such thing, and I went straight home into quarantine.

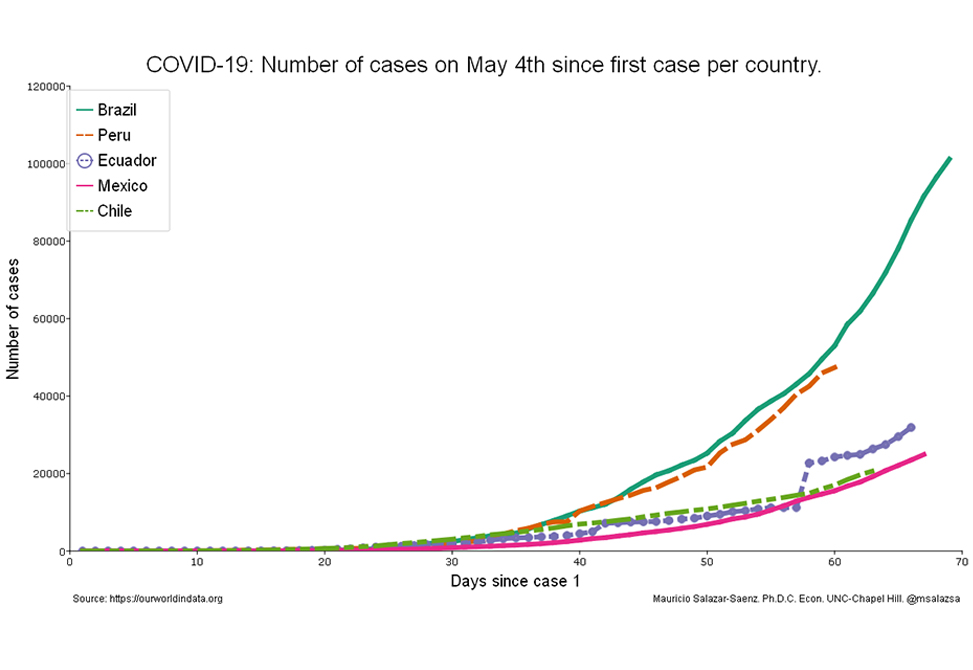

A trip from Ecuador to Europe would normally take less than 20 hours, but it took me 44 this time. When I got there, the number of confirmed cases in Ecuador had increased by several hundred. Today, there are over 29,000 confirmed cases, with many more undetected. Officials speculate that over 10,000 people have died, which is 10 times the amount of confirmed deaths. Devastating pictures from Ecuador’s biggest and most socio-economically divided city of Guayaquil have begun to circulate across international media. For a while, community spread was out of control, and the national health and funeral services collapsed as the province struggled to contain the outbreak. The authorities could not remove the overwhelming amounts of people who were dying in their homes fast enough which led some people to burn corpses in the middle of the street. Hospitals had to turn away even the illest patients as death rates escalated quickly. This has served as a grim reminder of how deeply-rooted histories of the class divide, race, and an unexpected disaster can intersect most devastatingly.

While I am no longer in Ecuador, I am keeping in touch with people there. My friend in Quito is quarantined until the end of May and says that Quito is still quietly calm, as they have managed to somewhat contain the spread, except in the poorest parts of the city. In contrast, Don Juan remains without confirmed cases. Community members have self-organized and enforced their own rules, thus rejecting stereotypes such as them being lazy and stupid by actively organizing and taking measures into their own hands. The curfew has made it difficult to go fishing but every few days some of the men went to get enough food for others. The vegetable truck that would normally come twice a week is not always allowed to enter, as men also decided to protect the entrance of the village from anyone entering unless they’re local. At the onset of blocking off the road, they first started with throwing a tree trunk down in the street so people couldn’t pass. After the police removed the tree, about 10 men spent 24 hours a day up at the top of the hill at the entrance into the village not allowing people to come through. Eventually, they upgraded to make a gate that they could pull up and down, like a bamboo trunk. Then they installed a donated full-size gate where only three men guard the entrance. They are spraying people down with a Clorox solution when they enter the town, and a truck has come several times to spray the village with it.

The COVID-19 pandemic will have differential effects, and it will be particularly interesting to see how a community that only so recently dealt with a catastrophic event will be affected in the long-run. Quarantine-imposed restrictions might have particular consequences for household relations and violence in a context where large families are forced to be locked down in a small 2-bedroom house with a hot tin roof and very high temperatures. A lot of people are struggling with resources, as they are not getting sufficient income or food, which normally comes from selling fish, produce, or maintaining gated tourist communities. It will be a long recovery from an unexpected public and mental health crisis.

I have lived through a unique moment during the initial few days of the pandemic together with the people which has brought us all closer, though physically further apart, building connections that have been maintained across continents. I’m eager to return and help with the post-COVID relief, though it is unclear not only when it will be, but also how it will look. The nature of fieldwork and the role of an ethnographer in a post-coronavirus context might never be the same.