Colombia and the World in the Time of COVID-19

By Mauricio Salazar-Saenz

Mauricio Salazar-Saenz is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

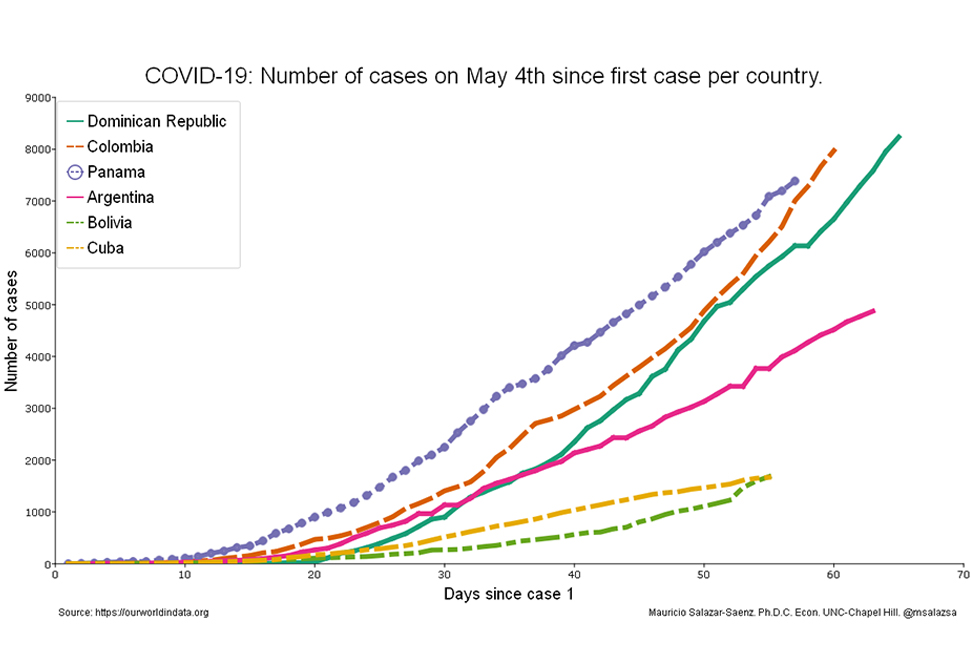

Chart depicting the number of cases on May 4th since the first case per country.

Countries include the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Panama, Argentina, Bolivia, and Cuba.

Created by Mauricio Salazar Saenz, Ph.D.C. Econ. UNC-Chapel Hill.

Data received via Our World in Data

In the country with more than 60 years of armed conflict, COVID-19 is the first time that the whole country shut down. This time, the menace is not the drug traffickers alarming the Colombian state, or the guerrilla groups surrounding the main cities, nor the paramilitary displacing peasants to assure more land to landlords. This time the invisible enemy incubates inside our bodies for 14 days, infecting those around us.

In early March, the rightwing president was advised by experts with a poor academic reputation to not shut down the country. Nonetheless, the mayors of the three largest cities: Bogota, Medellin, and Cali, implemented a mock quarantine to evaluate the protocols in a country with no previous lockdown experience. A power struggle started as the president claimed that he is the only one with the authority to shut down the economy, a conflict similar to the one seen in the US.

Then something unexpected happened, maybe the images reflecting the crisis in Spain and Italy made the president declare a national quarantine: if countries with more resources than us were suffering in that magnitude, what makes us believe that we are immune? The borders were closed, and a national lockdown started on March 24th until April 27th, when manufacturers and construction companies returned to work with new safety policies to avoid the spread of the virus. On May 11th the president will reevaluate the need for a lockdown. Additionally, during the quarantine, the greater armed actors, guerrillas and the state, had made a truce to fight the invisible enemy by no fighting the visible ones.

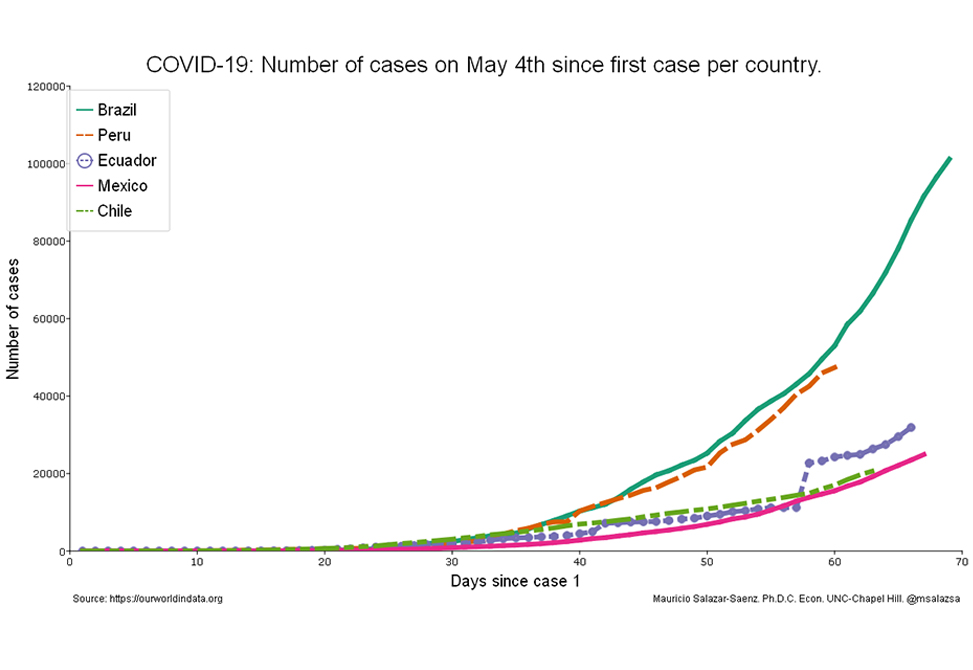

Chart depicting the number of cases on May 4th since the first case per country.

Countries include Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Mexico and Chile.

Created by Mauricio Salazar Saenz, Ph.D.C. Econ. UNC-Chapel Hill.

Data receieved from Our World in Data

Colombians shared a common destiny with the other Latin American countries: as a result of an underfunded healthcare system, the expected hit of the pandemic is much harder than in richer economies. When most countries in the region decided to start implementing national quarantines, to reduce the speed of contagion, Colombia was among the first to react. Chile and Mexico were the last countries to start quarantines, and initially, the presidents and ministers were making fun of this new flu. In Brazil, almost no measures were taken at the national level.

The results of the country’s timeliness on implementing a national quarantine are: Brazil has more infected people and deaths than China, followed by Peru which has numbers similar to Belgium, followed by Ecuador with infected people similar to Saudi Arabia, and Mexico and Chile complete the top 5 with about 25K and 20K infected people, respectively. The Dominican Republic is approaching 8.3K infected people, while Colombia and Panama have about 8K and 7.4K cases, respectively. Argentina, Cuba, and Bolivia complete the countries with more than 1K cases with 4.9K, 1.7K, and 1.7K, respectively.

In contemporaneous times, mankind has never faced such a difficult trade-off: don’t declare quarantines and expect a collapse of the health system, making people die massively or declare quarantines, flattening the contagion curve but increasing the unemployment. Because of the latter option, the World Bank expects world poverty to double after COVID-19.

It seems that without a vaccine or medicine, we will be living in this situation for more than a year. We don’t know how future malnutrition will weaken the immune systems of a new impoverished population, and hence how the fatality rate could increase due to that. What we saw at the beginning of April, was Guayaquil suffering like no other city in the world, with people dying on the streets and inside households without the personnel to remove the bodies. A society collapsing with no funeral homes open because the personnel of that industry was avoiding contagion. The only available measure to avoid a comparable situation is social distancing. After declaring national lockdowns, LAC governments also declare economic measures such as subsidies and transfers in kind to vulnerable populations, in a battle against time to provide people the incentives to stay at home.

In the current regime, we all eventually will get COVID-19, the big question is at what speed each society will get it, and how long can we fund, support, assume a national lockdown with limited country-level economic resources and a geometrical contagion rate that make individuals hard to understand the risk of an enemy that has shown to take any advantage to spread inside human societies.

In the meanwhile, Medellin remains at a very low speed and with a high air quality measurement, which hasn’t been seen in decades. My Spring Break became an undefined stance. I am finishing my semester doing remote teaching and grading, while I haven’t been able to see my family that lives in Bogota, previously at a distance that was 35 minutes away by plane but under the current circumstances seems infinite.