COVID-19 response as a time for Costa Rica to recommit to sustainable development

By Mary Little

Mary Little is an Associate Professor of Environmental Ethics and Development at the School for Field Studies in Atenas, Costa Rica.

Dona Nuria holding a vegetable at El Progresso Farm in Guápiles, Costa Rica.

One of the agrotourism offerings that provide environmental and socioeconomic benefits to families.

Now may be the moment for Costa Rica to focus on small-scale tourism

and sustainable agriculture to preserve biodiversity.

Photo credit: Anna Chah'

Costa Rica is known for its relaxed yet efficient way of life and the nation’s Covid-19 response has been informed by this cultural attitude. People have generally followed the stay-at-home orders and driving restrictions. These regulations were also relatively lax compared to other Latin American countries because cases have remained low and only 10 deaths have occurred to date. Being from the United States, I constantly take in the reports of the mismanagement of testing, personal protective equipment, and reopening there. It has shocked many here that of the approximately 10,000 Costa Ricans living in the US, 23 have died of Covid-19, more than twice as many as within this country of 5 million.

The near-collapse of the tourism sector is a visible reminder of how dependent Costa Rican’s economic health is on the global economy. When the International airport closed except for a trickle of flights, people were required to stay at home, and beaches and national parks were closed. As tourism has been effectively put on pause, the restrictions of people and cargo at the borders has also made people aware of their dependence on the global food supply. At some level, the pandemic has made Costa Ricans stop and reevaluate their relationship with relentless globalization. If this is the pause and wake up call to reassess our relationship with nature and globalization, it may also be the time for Costa Rica to reevaluate its relationship with the United States. Costa Rica has implemented exemplary policies such as national protection of 26% of its land and meets nearly all of its energy needs via renewable means. But as part of interdependent global markets, it has been caught between its green agendas and demands of neo-capitalism as usual.

Costa Rica’s relationship, perhaps reliance, on the US has allowed it to follow its ideals of being one of the few countries without an army and to achieve rapid rates of economic development. Accepting U.S. economic models began when the nation struck an agreement with the United Fruit Company to exchange land and tax-free exportation in exchange for the construction of a railway. That reliance was reinforced during the 1980s debt crisis. Attracted by the newly protected national forests and beaches, “green” tourism was proposed as a solution to generate revenue to repay the World Bank loans. The Costa Rican government was encouraged to provide investment incentives and tax breaks to appeal to investors. The government agreed to these terms and Costa Rica has become highly reliant on tourism, with 600,000 directly employed in the sector. The downside is that tourism is vulnerable to economic downturns and, as nearly no one had considering, pandemics. Where sustainable tourism has had positive environmental and economic impacts, overreliance on global travel has also made many regions of the country completely dependent on outside cash to maintain local economies. When international commercial flights ended, so did up to 90% of businesses in tourism towns like Arenal, Manuel Antonio, and Monteverde.1

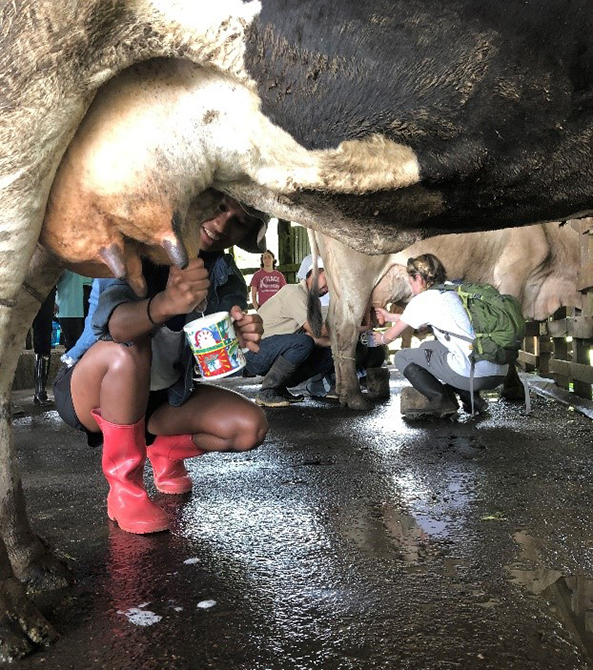

Photo Credit: Mary Little

In my research on tourism in Costa Rica over the past five years, I’ve found that the question of how to diversify revenue sources has been on the minds of many in the tourism industry. The more I’ve visited rural areas, the more examples of agrotourism I’ve experienced. They demonstrate that they can provide attractive opportunities on the tourism and food security fronts by creating a combination of the production of coffee or other crops, mixed with tours and lodging that provides an ecological and economic balance. It also allows people in rural areas to slowly enter tourism without large loans that can prove ruinous. Visitors are expressing a growing appetite to reconnect with nature and have authentic, local experiences, including learning about food production. The pandemic may reduce the appeal of large resorts and cruise while making the possibility of connecting with people from another culture and nature more attractive. As cautious reopening begins here, national tourism is being encouraged. Perhaps Costa Ricans will place a greater value on what the rest of the world comes to this country to experience and less desire for a Disney vacation and shopping spree in the US.

As Thomas Friedman wrote in a recent opinion piece in the New York Times, “Globalization is inevitable. How we shape it is not.”2 This pandemic appears to be reinforcing Costa Ricans’ sense of uniqueness in their commitment to public services and environmental protection. Hopefully, it is that reinforced respect of the local and distinctive that will continue beyond this immediate pandemic response. When we can once again travel, we chose to immerse ourselves in communities and experience their realities while promoting economic and environmental health. Relying on local resources for food and travel can make us more committed to living within our ecological limits. My greatest hope is that the Costa Rican government and people will take this opportunity to reinforce and protect that makes this country unique by enacting development policies that harness globalization that is beneficial for its citizens and remaining biodiversity.

Footnotes:

1. Murillo, Álvaro. “El turismo pequeño ve el precipicio: “tratamos de ser optimistas, pero puede empeorar”, Semanario Universidad, May 20, 2020.

2. Friedman, Thomas. “How we Broke the World: Greed and globalization set us up for this disaster.” New York Times, May 30, 2020.