Quarantined in Buenos Aires

By Liz Mason-Deese

Liz Mason-Deese received her BA in Anthropology from UNC in 2005 and her PhD in Geography in 2015. She currently resides in Buenos Aires where she works as a freelance translator.

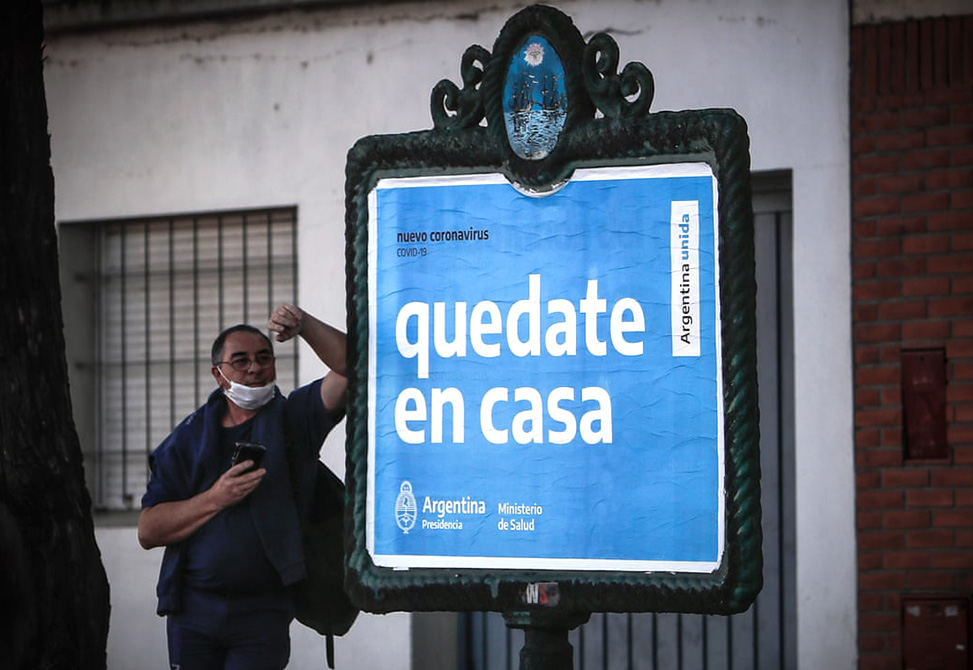

A man waits in front of a poster with a message from the government to ask

people to comply with quarantine rules, in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Photograph: Juan Ignacio Roncoroni/EPA from The Guardian

Walking along the usually busy streets of Boedo, a traditional, residential Buenos Aires neighborhood known for its tango and literature, the first thing I notice is the silence. The first two produce shops I pass by are closed, as is the butcher’s, the pasta shop, and the fishmonger. The only place where I see other people is lined up to enter the pharmacy. I finally find an open shop and but quickly realize that prices have already more than doubled in the week since the quarantine began. Ultimately, I decide against spending half of my daily wages on spinach and a few apples, the only remaining produce in stock, and head home empty handed.

Argentina has had one of the swiftest and strictest responses to COVID-19 in the Americas. President Alberto Fernández issued a decree closing the border and canceling large events in early March, which led to a nationwide shelter-in-place order on March 20th. Only a strictly defined set of “essential workers,” limited to those who guarantee the food supply, health care, and public safety, are allowed out. The majority of residents are limited to their homes, only allowed to go to the closest grocery store, pharmacy or medical locations for emergencies, where we are required to wear masks in these enclosed spaces.

Staying off the streets does not come easily for us in Buenos Aires. Less than two weeks before the quarantine started, hundreds of thousands of us marched through the downtown streets as part of the international feminist strike, protesting against gendered violence, inequality and exploitation, and for our right to legal, safe, and free abortion. Only a few weeks later, on March 24th, the anniversary of the military coup that brought a brutal dictatorship to power in 1976, and a historical day for human rights struggles in the country, we find ourselves confined to our homes and unable to hold the usual multitudinous march to declare “never again.” Instead, each household fashions their own white handkerchief, the symbol of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, and hangs them on their balconies, windows, rooftops, sharing images on social media and chanting from our homes in what has become the new form of protest.

At the same time, there have been a few right-wing protests, also from their balconies, against the quarantine measures. However, the majority recognize that the government’s actions are necessary, not only because of the severity of the virus itself, but also because of the condition of Argentina’s healthcare system. After decades of neoliberal policies, the public system is drastically underfunded, leaving us with a public-private patchwork of medical facilities that varies greatly by neighborhood or region, one’s job and socioeconomic status. The previous government of Mauricio Macri was notorious in this regard, leaving hospitals half built in some of the country’s poorest areas. Medical workers have already held protests decrying the long hours, low pay, and lack of PPE and other necessary medical equipment. COVID-19 is not the only thing that kills.

On March 30th, we took to our balconies again, this time to protest against the alarming rise of femicides. Since the quarantine began, an average of one woman a day has been killed. “Stay at home” means that women are stuck in homes with their abusers, with few escape routes. With schools closed, friends with children tell me that they are working nonstop, feeding, educating, entertaining their kids, while also doing their own jobs and regular domestic work. Yet the feminist movement continues putting forth proposals for a feminist response to the crisis, pushing the government to provide resources to address domestic violence and building our networks of mutual aid.

After two weeks, I finally get fresh produce, I sign up for a weekly box of fresh fruits and vegetables that comes from a collection of local farms and is delivered directly to my door. These sort of arrangements – delivering produce direct from the farmers – multiply, allowing consumers to avoid the speculation in food prices that we have seen in the major supermarket chains, while allowing small farms to continue functioning. It also highlights problems that existed in Argentina well before the pandemic: the rampant inflation, especially of food items and the inherent limitations of an agro-export model. For decades, much of the population has relied on this “popular economy” to get by, working informally or in cooperatives, obtaining goods through informal markets and food from soup kitchens run by social movements.

Now, with the coronavirus crisis, more people across the country rely on those small agricultural producers, community soup kitchens, or other forms of mutual aid organized by social movements, in order to have enough to eat. With nearly half the population working informally and with the country coming off two years of a recession, fears of the economic impact of the crisis are just as great as fears of the virus itself. In an effort to alleviate the worst of these effects, the government implemented a series of extra benefits for the unemployed, informal workers, self-employed, and retired. The need was so great that the people started lining up the day before the benefits were to be released, waiting outside of banks overnight to be able to withdraw the money.

Meanwhile many continue working because they have no other option and because they are considered “essential” for the rest of us. The most notable of these are the delivery workers, working for Apps such as Rappi, Uber Eats, or PedidosYa, who, as ‘independent contractors’ have few guaranteed labor rights. On April 22th, those workers went on strike demanding pay increases and guaranteed benefits for risking their lives so that the rest of the population can stay at home. Subway workers have also organized work stoppages, decrying the lack of protective gear from the city government and inconsistent sanitation of subway stations. In one of my weekly grocery runs, I noticed an increase in the number of people sleeping on the streets.

A friend working in a shelter for homeless youth in the city of Buenos Aires tells me about the dire conditions: overcrowded, lack of cleaning products and protective gear, and, because of the city government’s incompetence, much of the staff hasn’t been paid in months. Another friend who works with incarcerated women tells me about the situation in the country's prisonswhere protests over the lack of cleaning supplies and hygienic conditions were met with repression both of prisoners and their family members, resulting in the death of at least one prisoner.

Meanwhile, the first cases of COVID-19 were recently reported in Villa 31, the slum behind the city’s major train and bus station. With much of the neighborhood lacking clean drinking water and electricity, and often a dozen people sharing a single, bathroom, preventative measures such as hand washing, and social distancing are near impossible. These inequalities make it so that the virus poses an especially big risk here. But could this crisis also be an opportunity? Fernández has proposed an extraordinary tax on the country’s largest fortunes, in an attempt to make the wealthy pay for the crisis, while continuing to provide financial assistance for the popular economy workers to stay at home.

A campesino leader was recently appointed as the director of the Central Market, leading to hopes that this will lead to lasting changes to the food system. Meanwhile, I stay at home and order face masks from a cooperative, I do an online Pilates class with comrades from my feminist collective and participate in video conferences to try to organize mutual aid and to cheer each other up, while we anxiously await the day that we can be on the streets together again.